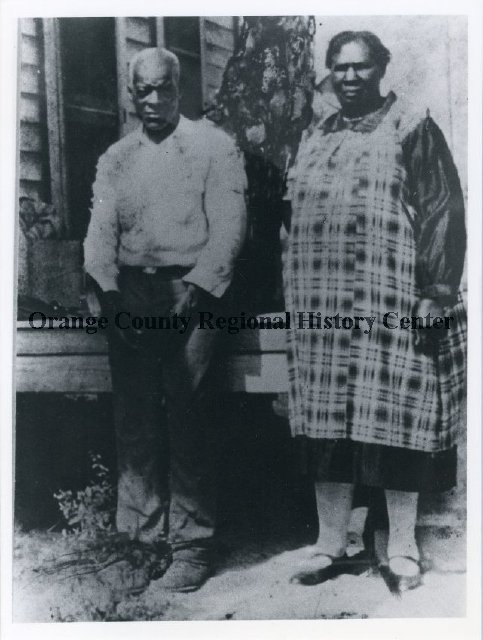

Jonestown was a Black community near Greenwood Cemetery comprised mostly of small houses and shacks. Founded in roughly 1880 along East South Street the name was inspired by Sam and Penny Jones, who lived along the banks of Fern Creek and were rumored to have been its first residents.

Most Jonestown residents worked as laborers but that wasn’t the rule. A man named Milo Cooper owned a barbershop on East Pine Street and a woman named Ellen Paine was a cook at the Duke Hall boardinghouse. E.F. Wooden ran a grocery store.

Jonestown was located mostly in a low-lying area along Fern Creek that flooded frequently. It had two churches, one school, one store, and 76 homes at its apex in 1939 before it was hit by a huge flood that year.

By 1939, the City was already building public housing for Black residents on the west side of Orlando’s downtown in the Parramore District, with the railroad as the unofficial dividing line as with most towns in the country, which was comprised of the Callahan, Lake Dot, and Holden neighborhoods. In the early 1900s, Callahan Neighborhood, once known as “Pepperhill,” was renamed in honor of Dr. Jerry B. Callahan, the first Black physician to practice at the Orange County General Hospital.

Parramore was named after James B. Parramore, a confederate soldier and former Orlando mayor that had plotted the area in 1881 for the City of Orlando.

The top-down systematic segregation of Orlando’s Black communities began officially in 1923 when the City’s zoning commission began designating separate areas for Black-owned residences. That act of redlining still has implications in how our city operates today, more on that HERE.

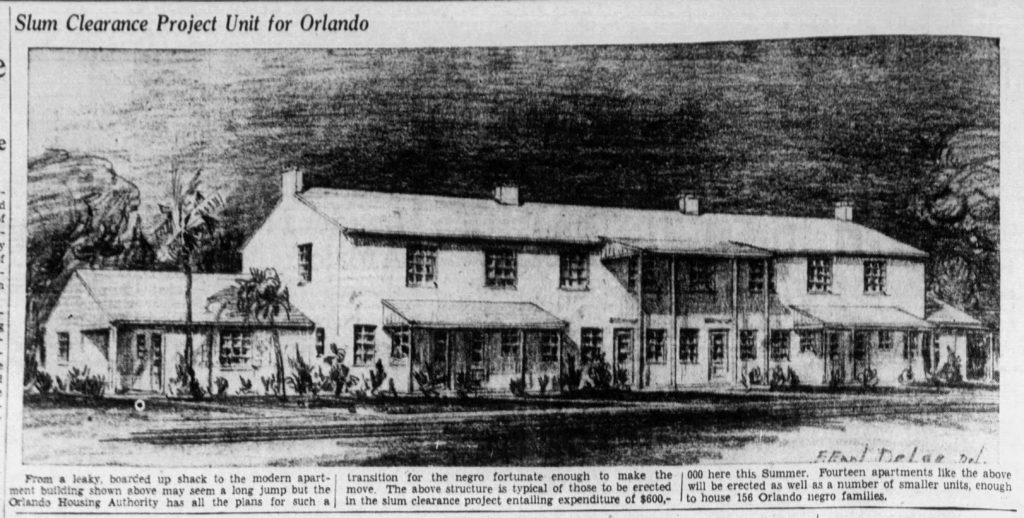

Griffin Park, which we’ve written about previously HERE, was erected on the site of a drained swamp, and Carver Court was built on top of a former city dump yard. As an aside, the Carver Dump used to be, allegedly, perpetually on fire and people used to have to wear gas masks and turn their car headlights on when passing by due to the dense smoke from the burning trash pile. People called it “Little Vesuvius” for obvious reasons. Carver Court was designed by the City to house roughly 85-150 Black families and was offered to Jonestown residents first, before being offered to other families and people of color.

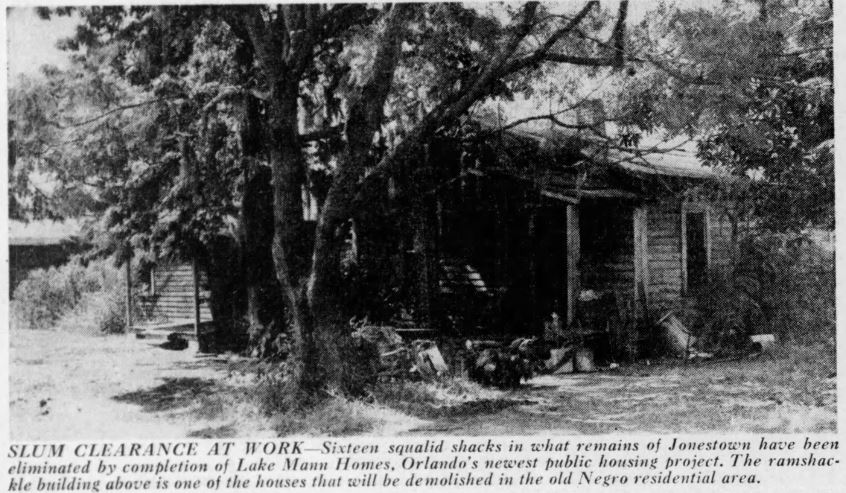

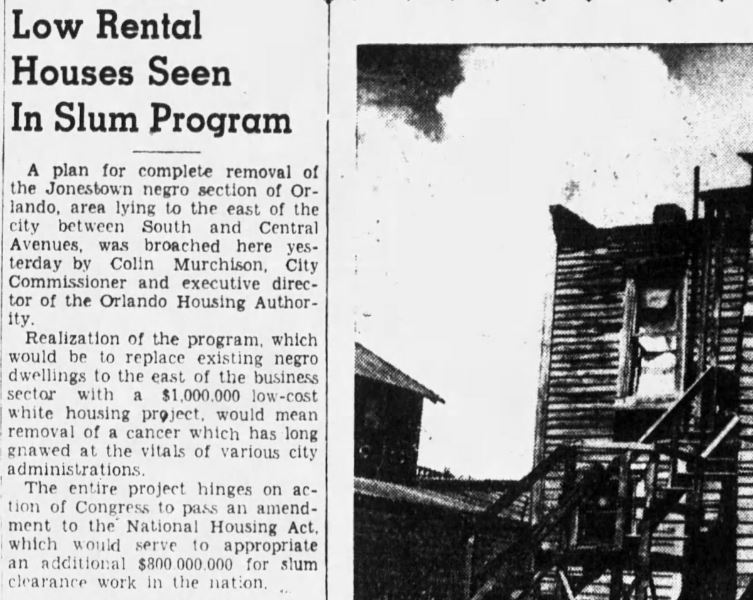

White residents called out against the spending declaring it unfair that struggling white families were not receiving the same treatment and demanded a similar area for low-income white families. Simultaneously, the City was under constant pressure to relocate Jonestown residents to the west side of town as the neighborhoods around it became increasingly developed and desirable. Jonestown was seen as a blot on downtown Orlando’s residential neighborhoods and even journalists minced no words when referring to the neighborhood.

In case you missed it in the article above, Murchison, the man referring to Jonestown as a “cancer,” was a commissioner and the executive director of the Orlando Housing Authority. That same article pictured above quotes Murchison as saying, “A housing project with a million dollars of government money is the only way to clear the colored people out of that part of our residential districts.”

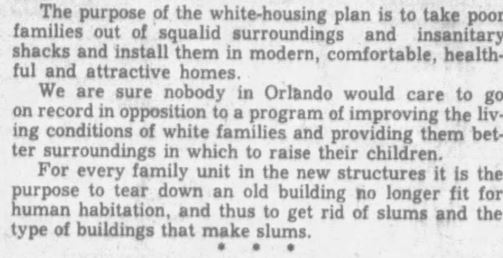

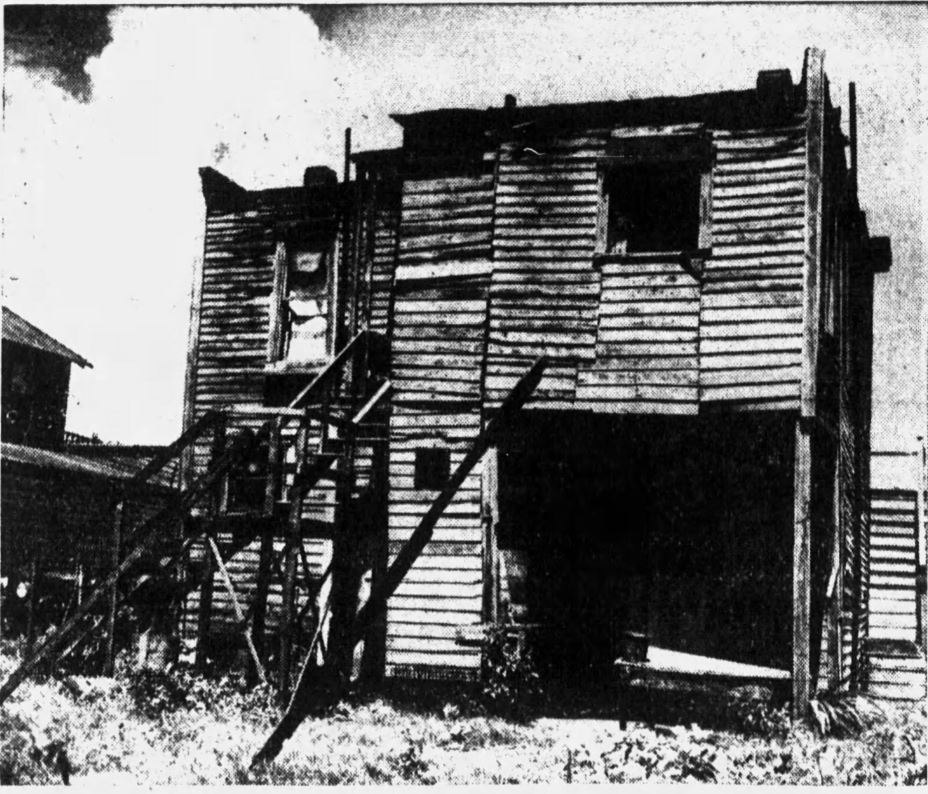

The City Commission started a campaign of “othering” the Jonestown community and referring to the Black-owned homes as “tumbledown cabins” and “shacks.” The conversation in the surrounding neighborhoods became one of the “liberation” of the residents from squalid conditions, like in this column from the Orlando Morning Sentinel.

City Council voted to allow The Housing Authority of the City of Orlando, the rights to develop and administer a “low-rent, white housing project” on the Jonestown property. Which you can see for yourself by clicking the link below:

By agreeing to build the new whites-only housing project, the City was also condemning the Jonestown community to demolition, and declared the buildings as unfit and unsafe for human dwelling. The city did so by either acquiring the land themselves and knocking the houses down, or by compelling the owners to “voluntarily demolish” their own homes.

Mayor William Beardall was responsible for the relocation of the Black residents to the west of Orlando in the city’s “negro area” (now known as Parramore) and insisted that it be replotted and expanded to house transplants, and was quoted saying, “It’s a fact that if the negroes live in unsanitary conditions, then the whites are forced to live the same way, for the negroes cook, wash, and take care of white children. This isn’t just a problem of putting in a white housing development. The white housing project is predicated on the negro problem. More room must be found for the Orlando negroes, room where the negroes and private investors can build the proper kind of living quarters.”

In 1940, a white housing project called “Reeves Terrace” was built on the site, mostly for low-income white residents and war families. The city purchased the last Jonestown home in 1962 and demolished it as soon as the former homeowner moved out.

I love that you are educating people about our city’s shady history. Hopefully this will provide insight as to how the actions set forth by past leadership are the direct result of what’s going on today. It would be nice if articles such as these could pave the way for compassionate discourse and eventual change; thank you for your role in this.

Thank you Bungalow for publishing stories about Orlando history. It is very interesting, and helps us learn and improve.

Thank you for this story. We need to know more about this kind of history so we can do better.